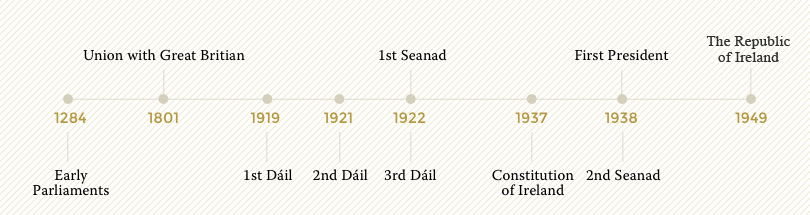

The first meeting of Dáil Éireann took place on 21 January 1919. However, parliaments, in various forms, were a feature of Irish life from the 13th century up to 1801.

Early Parliaments

The Normans, who began to settle in Ireland in 1169, were the first to give Ireland a centralised administration. The first Irish Parliament for which there is a definitive record met on 18 June 1264. The parliament met in Castledermot, County Kildare, then an important administrative centre. The meeting was not a parliament in the modern sense. The members were not elected representatives but land-owning knights and jurors. They met to inquire into whether Archbishop Fulk Bassett de Sandeford had the right to hold courts and exercise justice.

It appeared that the archbishop had been taking it on himself to deal with matters that should have been matters of state. This brings us to a very contemporary theme of church-state relations.

There is a written record of the meeting in the Black Book of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin. On 18 June 2014, the Seanad commemorated the 750th anniversary of Ireland’s first recorded parliament.

The Irish Parliament, in various forms, continued to function for more than 500 years. These included the General Assembly of the Confederation of Kilkenny from 1642 to 1649, the "Patriot Parliament" of 1689, and "Grattan's Parliament" from 1782 to 1800. These assemblies, however, all lacked the principle on which Dáil Éireann was founded in 1919. This was that all legislative, executive and judicial power had its source in, and was derived from, the sovereign people of Ireland.

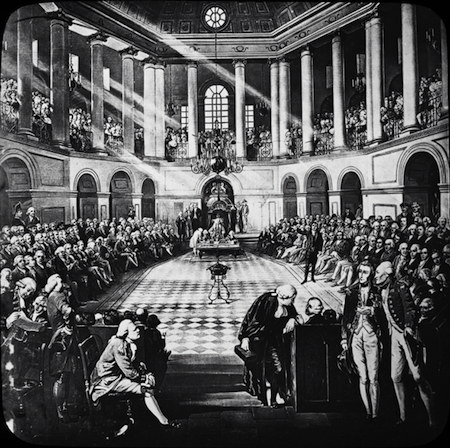

Henry Grattan addressing the Irish House of Commons, after Francis Wheatley / Courtesy of whytes.com

Over the years, the Irish Parliament met in many different locations, including Dublin Castle. In 1729, construction began on what was to become the first purpose-built two-chamber parliament house in the world. It mirrored the British Parliament, with a House of Commons, presided over by a speaker, and a House of Lords consisting of Irish peers and Church of Ireland Bishops.

Union with Great Britain, 1801

Following the French Revolution and the Irish Revolution of 1798, the Government in London wanted to bring Ireland under its direct control. It persuaded the Irish Parliament to pass the 1800 Act of Union, effectively voting itself out of existence.

I have heard of Parliament impeaching Ministers, but here is a Minister impeaching Parliament.

The Irish Parliament came to an end in 1801, when the Act of Union created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and amalgamated the two parliaments. Irish Members of Parliament and peers now took their seats in the Palace of Westminster and Parliament House was sold to Bank of Ireland.

The Great Parliament of Ireland, elected 1790 / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

With 100 seats in the House of Commons and 28 in the House of Lords, Irish elected representatives were very much in the minority. The day-to-day administration of Ireland was in the hands of the Lord Lieutenant, who was the King’s representative, nominated by the United Kingdom Government.

The closure of the Irish Parliament contributed to an economic downturn in Dublin. The Parliament sessions had drawn Irish peers, with their families and servants, to reside in the city for a portion of each year. After the Union, many of these families sold their Dublin mansions and spent more time in London.

The First Dáil, 1919

After the Easter Rising of 1916, and the executions that followed it, public opinion in Ireland turned against the British crown. In the 1918 general election, Sinn Féin, the nationalist party, won 73 of 105 Irish seats in the House of Commons. However, Sinn Féin had pledged not to sit in Westminster but to create an independent assembly in Ireland.

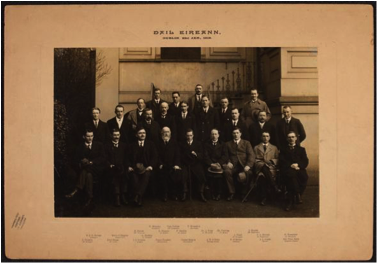

The party made good on its promise by inviting all elected Irish representatives to attend a parliamentary assembly in Dublin. On 21 January 1919, the first Dáil met in the Round Room of the Mansion House. The room was crammed with onlookers and journalists, who greatly outnumbered the 27 Members who attended. Unionist and Irish Party MPs declined to attend and are listed in the Official Report as “as láthair” (absent). Many Sinn Féin Members were listed as “ar díbirt ag Gallaibh” (banished by foreigners) or “fé ghlas ag Gallaibh” (imprisoned by foreigners). Among these was Countess de Markievicz, who was imprisoned in Holloway prison, London.

Members of the first Dáil outside the Mansion House, 22 January 1919 / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

During the two-hour sitting, Dáil Members adopted a Constitution and read out a Declaration of Independence, first in Irish, then in French and, finally, in English. This declaration ratified the Irish Republic that had been proclaimed on Easter Monday 1916 and ordained “that the elected Representatives of the Irish people alone have power to make laws binding on the people of Ireland, and that the Irish Parliament is the only Parliament to which that people will give its allegiance”.

We ordain that the elected Representatives of the Irish people alone have power to make laws binding on the people of Ireland, and that the Irish Parliament is the only Parliament to which that people will give its allegiance

The Dáil then called on the free nations of the world to “support the Irish Republic by recognising Ireland's national status and her right to its vindication at the Peace Congress.” It also laid out a democratic programme, declaring the desire that Ireland be ruled “in accordance with the principles of Liberty, Equality, and Justice for all, which alone can secure permanence of Government in the willing adhesion of the people.”

The first meeting of the Dáil in 1919 had coincided with the start of guerrilla attacks against the British security forces, which escalated into the War of Independence. In September, the Dáil was declared a dangerous association and was prohibited, but continued to meet in secret.

To learn more about the First Dáil, visit www.dail100.ie.

The Second Dáil, 1921

In 1920, Westminster passed the Government of Ireland Act, which granted home rule to Ireland. However, it created not one but two parliaments, one in Dublin for Southern Ireland and a Northern Ireland parliament based in Belfast. It also asserted Britain’s sovereignty over Ireland. The War of Independence continued.

The Parliament of Southern Ireland held its inaugural meeting in the Royal College of Science for Ireland, now Government Buildings / Courtesy of the Department of the Taoiseach

In May 1921, a general election was held to fill the 128 seats in the new House of Commons of Southern Ireland and 52 seats in the Northern Ireland House. The First Dáil decided to dissolve and regard this election as an election to Dáil Éireann. Sinn Féin took 124 seats in Southern Ireland and six in the North.

In June, the new Parliament of Southern Ireland met, but only the four non-Sinn Féin Members of the new House of Commons turned up. The parliament adjourned sine die and was dissolved the following year.

In July, a truce was called in the War of Independence, but the negotiation of a final settlement was deferred.

A crowd gathered outside the Mansion House, Dublin, 8 July 1921 / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

On 16 August 1921, the Sinn Féin elected Members convened the Second Dáil, again in the Mansion House. One of the first items of business was to discuss the truce and appoint a delegation to go to London and negotiate a binding treaty. The delegates signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December, but it was subject to ratification by the Dáil.

The Dáil met in the Mansion House, Dublin, August 1921 / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

If I am a traitor, let the Irish people decide it or not, and if there are men who act towards me as a traitor I am prepared to meet them anywhere, any time, now as in the past. For that reason I do not want the issue prejudged. I am in favour of a public session here now.

In a series of Dáil sittings starting on 14 December, this time in University College Dublin on Earlsfort Terrace, Members debated the treaty. On 7 January 1922, the Dáil ratified the treaty by 64 to 57 votes and the President of Dáil Éireann, Eamon de Valera, announced his intention to resign.

I have seen the stars, and I am not going to follow a flickering will-o'-the-wisp, and I am not going to follow any person juggling with constitutions and introducing petty tricky ways into this Republican movement which we built up.

This split in the Dáil reflected a bitter division in Sinn Féin that eventually broke up the party. The Irish army also split, and the anti-Treaty side refused to recognise the Dáil and began preparations for war by amassing arms and occupying strategic buildings.

Under the terms of the Treaty, a provisional Government was established. Although the Second Dáil was not recognised by the British Government, it continued to sit, and operated in parallel with the provisional Government.

A general election was held on 24 June 1922, and the pro-Treaty Sinn Féin side won 58 seats to the anti-Treaty side’s 35. Before the end of the month, attempts to unite the army had failed and the Civil War had started.

On 9 September 1922, the Third Dáil met in Leinster House, without the anti-Treaty Members, who boycotted it. In October, the Dáil adopted the Constitution of the Irish Free State, which defined the Oireachtas as comprising the Dáil, the Seanad and the King. The Irish Free State, with jurisdiction over twenty-six of the thirty-two counties, came into existence in December 1922.

I think that Kings in Constitutions are like kings in chess, and that really the important piece in the Constitution is that person whoever it may be that is chosen to be the Premier or President

The Civil War petered out in 1923 and, in 1927, a number of anti-Treaty politicians took the oath and entered the Dáil.

The First Seanad, 1922

Before the Act of Union, the structure of the Irish Parliament mirrored that of the British Parliament, with a House of Commons and a House of Lords. The Parliament of Southern Ireland established in 1920 was also to have an Upper House, to be known as the Senate, with 64 Members. In the general election of 1921, 40 Senators were selected but many boycotted the Parliament, and only 15 attended the first meeting. The Parliament of Southern Ireland failed to function and was abolished in 1922.

The Constitution of the Irish Free State, which the Third Dáil adopted in 1922, provided for the establishment of an upper house to be known as Seanad Éireann and consisting of 60 Members. The Constitution provided that the Seanad should be composed of citizens who had done honour to the nation by reason of useful public service or who, because of special qualifications or attainments, represented important aspects of the nation’s life.

The Seanad of the Irish Free State met for the first time on 11 December 1922. One of its first debates was on the need to end the acts of violence that were taking place in the country.

We drifted from abuses into fighting, and we went on from that to the burning of houses and murder, and from that to reprisals, all the time being shocked at each thing that happened, but whatever happens now we take it as a matter of course.

Seanad Members included former unionists and holders of British hereditary titles, and the anti-Treaty forces in the Civil War burned many of their houses. Even after the Civil War there were mixed feelings about the need for an Upper house. In 1928, Deputy Seán Lemass said in the Dáil, “this bulwark of imperialism should be abolished by the people's representatives on the first available opportunity that they get.”

Relations were not improved when, in 1932, the Seanad opposed legislation to remove the oath which Members of the Oireachtas had to take. The First Seanad held its final sitting on 19 May 1936 and was abolished soon afterwards.

Constitution of Ireland, Bunreacht na hÉireann, 1937

By the end of 1936, the Constitution of the Irish Free State, which the Dáil had adopted in 1922, remained in place but had been amended 27 times. A number of amendments had diminished and, eventually, abolished the office of Governor General, the King’s representative. All references to the king had been removed from the Constitution, the university constituencies in the Dáil had been removed and the Seanad had been abolished.

On 1 July 1937, a new Constitution of Ireland, Bunreacht na hÉireann, replaced the Constitution of the Irish Free State. The new Constitution became the basis for the modern Oireachtas and the functions and powers of the Oireachtas derive from it.

The Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution gave the name Éire, or, in the English language, Ireland, to the State and asserted that "Ireland is a sovereign, independent, democratic state." The head of Government would be known as the Taoiseach, and a new Seanad Éireann was provided for. The Constitution also created the office of President of Ireland. Read Bunreacht na hÉireann here.

The First President, 1938

Dubhglás de Híde (Douglas Hyde, nom de plume "An Craoibhin Aoibhinn") was inaugurated as the first President of Ireland on 25 June 1938.

Today the Seanad meets in the former ballroom of Leinster House

The general election for the new Seanad took place in March 1938 and the Second Seanad held its first sitting on 27 April 1938. In 2013, a proposal to abolish Seanad Éireann was rejected in a referendum, and the Seanad remains in place today.

The Republic of Ireland, 1949

Although Ireland’s links with Britain had been diluted, it remained part of the Commonwealth and the British monarch was still the titular head of Ireland’s external relations. This was a source of embarrassment abroad, for example in 1947 the Irish ambassador to the Vatican was kept waiting in Rome for three weeks to have his credentials signed by the King.

This Bill will end, and end forever, in a simple, clear and unequivocal way this country's long and tragic association with the institution of the British Crown

The Republic of Ireland Act 1948, which came into operation on 18 April 1949, severed the final link with the British Monarchy. It stated that "The President, on the authority and on the advice of the Government, may exercise the executive power or any executive function of the State in or in connection with its external relations." It also stated that the description of the State is “Republic of Ireland”, however the name of the State remains Ireland in accordance with Article 4 of the Constitution.

Read the Dáil Second Stage debate on the Republic of Ireland Bill 1948 here.

Last updated: 7 October 2020